need to correct: should be University of Southern California

this will need link to spotlight

Link to appendices later

Need image

What are the risks and opportunities? Veteran co-creators have developed many strategies, informed by a long history of defining collective protocols, practices, and pathways that hold partners accountable to each other.

From our in-depth interviews we surfaced key practical lessons for co-creating media. These will be presented in this chapter before we articulate a more detailed consideration of co-creation within communities (in-person and online), across organizations and with non-human systems (in Parts 3-6).

These lessons and strategies are informed by a long history of defining collective protocols, practices, and pathways that hold partners accountable to each other. Co-Creation is a whole greater than the sum of its parts. In this part we summarize the risks of co- creating as identified through our interviews. We then outline key strategies of co-creation, from starting points, to manifestos, to contracts, the balancing process with outcomes, complex narrative structures, safety, appropriate frameworks, training and digital literacy, and finally to new models of funding and iteration.

Co-creation carries risks, and can be misused for profit and power.

For many artists, journalists, professionals, and decision-makers, the notion of co-creation threatens to compromise vision, authority, standards, and the rigor of established systems that support talent and expertise. Misapplied co-creative processes can dilute ideas to the lowest common denominator. Meanwhile, vulnerable communities who have been excluded historically from meaningful participation in professional media-making often express concern that the term, co-creation, can become simply a smokescreen for continuing extractive and exploitative practices. Finally, there’s the risk of the term being swallowed up and twisted by the cyclone of profit-seeking marketing and corporate domination.

The first risk of co-creation is that it may lead to a lack of high-quality storytelling or muddled decision-making processes that threatens editorial control and artistic integrity. Artists, academics, and professionals recoil at art by committee. Fred Dust, of the pioneering California-based design firm IDEO, admits that early on they found crowdsourcing projects often resulted in the lowest common denominator prevailing. Reviews on the popular Yelp website, for example, might average out a wide range of meaningful user ratings into a meaningless middle score.

From an artistic perspective, with co-creation, “the risks are totally incoherent narratives,” said Jennifer MacArthur, a documentary producer. She believes that results become so generalized and non-specific that they are “outside of anybody's shared experience or understanding [and] don’t resonate at all.” Tabitha Jackson, director of the Documentary Film Program at Sundance Institute, moderated a panel on the Art of Co-Creation at the 2018 Skoll World Forum. She identified the tension of authorship at Sundance, where “we're supporting the independent voice, and there is something to a singular, identifiable, distinctive voice that we value in the arts.”

For journalists, co-creation threatens the firewalls that guard the fourth estate. “A journalist's job is to be a skeptic at heart,” said Malachy Browne of The New York Times. While he was comfortable describing journalists’ relationships with some whistleblowers and sources as collaborative and co-creative, he emphasized that there is a need to maintain some distance:

particularly with investigative journalism. There's a lot at stake when you're interviewing witnesses. A journalistic instinct will give you a sense of when things are okay, but there are certain questions that you have to ask. That is more interrogation and interview than a co-creative process.

Meanwhile, Grace Lee, a documentarian, shuddered at:

[the idea of] thinking of all the people that would have to come to the table — including people I do not want to talk to [...] How do our own biases prevent us from actually having that diversity of opinion? I think about that a lot. Especially right now, because things are so extreme.

Collective processes can trip up strong, focused vision, and accountable leadership. The co-creative hope may be to flatten hierarchies, generate equity and equality, but the “tyranny of structurelessness” can take over, as the American activist and political scientist, Jo Freeman famously described her experiences with leaderless feminist collectives in the 1960s in an essay called “Tyranny of Structurelessness”. A nameless, undefined hierarchy may emerge instead, which can be even harder to hold accountable.

A panel on “The Art of Co-Creation: A Storytelling Model for Impact and Engagement” at the Skoll World Forum 2018, Oxford UK.

The promise of co-creation with, and within, communities and across disciplines can heighten expectations of trust, commitment, responsibility, and especially the duration and sustainability of co-created projects. Not everyone can commit equally to projects. The sharing of resources, time, credit, and responsibility of a project all need to be examined and negotiated in complex ways.

In other cases, it’s more an issue of clashing agendas. Lisa Parks, a digital-media scholar at MIT, has attempted co-creation with computer programmers and community partners on projects that were very challenging and that did not always come together in the ways that people hoped or expected. Parks reported:

We learned many things, but how do you go forward in a so-called collaboration or co-creation when you have really different demands placed on you in terms of your institutional position, or … what you feel you personally need to achieve in the project?

Ideals and reputations, both professional and personal, are at stake. Eventually, people might quit in frustration, never wanting to try co-creating again, said Michelle Hessel, a user-experience designer. “The most dangerous thing in a co-creative project is mistrust,” echoed artist Hank Willis Thomas. He commented:

That tension of people disagreeing is critical to the growth of a project. What was a great idea at the beginning [is now] a terrible idea, and only one person sees it. Now, four people have to come around to that. It's not going to always be easy for those four people to be like, ‘We started this, now you're saying we've got to change directions?’1

Co-creation can seem slow, and iterative, which means circling back when some team members want to move forward. It is inefficient and can lead to burnout. Further, the process sometimes means working with people and technologies you do not trust.

“Artists of color,” says Anita Lee, an executive producer at the National Film Board of Canada:

have historically been relegated to “community media.” They have carried a double burden of both representing a community and also of being made responsible to make work about a community. Often this work has also been undervalued as having less artistic merit. Today’s progress means a new generation of artists of color that have more opportunities to create work about anything. So single-authorship has often been denied — even stolen — does it make sense to forgo authorship now?

An adjacent threat is that co-creative projects can suffer from a lack of official legitimation, and be sidelined, for example, at museums. Salome Asega, an artist, said that work she has co-created has been restricted to “an ‘education’ bucket or a ‘public programs’ bucket.” She acknowledged that it can be hard to program process-driven work because of the challenge of documenting process.

Co-creative projects that are open to public participation and comment can be hacked from the outside. Queering the Map (2018) is a project that Lucas LaRochelle created to gather queer stories from around the world on a virtual map. It went viral almost immediately after its first media exposure. And then, just as quickly, the map was attacked by a bot. The perpetrators were “Trump supporters,” said LaRochelle.

“Queering the Map” (2018). Photo courtesy of Lucas LaRochelle.

The use of bots and other software can intensify the risk familiar to anyone reading publications or posts on the internet. These include reader-commentary on news sites and social media, where trolls and organized opposition can drive away productive contributors, forcing comments to be shut down or policed using draconian methods. Some news organizations have turned to AI tools for comment moderation. But even here there can be unintended consequences, with bots inadvertently removing 'reasonable' comments that somehow trigger the filter, leaving no room to for the writer to push back.

But more typically, as in LaRochelle’s case, AI and bots can generate seemingly human-authored texts. Jessica Clark, of Dot Connector Studio, offers an example drawn from the newsroom in which she describes the simple case of a bot that was built to generate a newsroom’s daily output of 40 social media posts that promoted its stories. While it might be cost-effective, Clark reported, “it takes out the editorial discretion of a social-media editor, and it potentially makes you look stupid if it's the middle of a crisis and you're posting about shoe-shopping or whatever.” And the results can be worse than that, warns Clark: “Say you create this social bot that learns from input. [You] can teach it to become a Nazi pornographer in a week — so it’s really about garbage in, garbage out.” This is the case with a Microsoft bot in 2016 that began parroting racist comments within 24 hours of launching.

The speed of swarm begets further speed, warned Fred Dust. “It becomes almost unrelenting.” Co-creative processes, then, can get out of control.

Co-creation can be misused. In the name of co-creation, people can steal ideas, profit from them, exploit labor, and obfuscate intent, rather than share or acknowledge accreditation and ownership. Then, co-creation becomes “the actual reification of the power of people who still have everything” said Jennifer MacArthur.

Similarly, participatory designer Sasha Costanza-Chock warned of media projects where all the “credit, visibility, awards, all end up just accruing to one person but then you call it co-creation so it gets this stamp of democratic legitimacy.” Or alternately, as Ellen Schneider stated:

There's this kind of perception, for many, that stories just kind of fall from somewhere.[…] They’re just there, and you're just around, and people who make them are lucky. They have a great job. They get to tell stories. And so unless and until we talk about that, up front, there will continue to be these huge violations or gaps or inequities that need to be really articulated and grappled with.

Co-creation can be misused as a form of tokenism, to tick off boxes, warned Salome Asega, especially “diversity boxes.”

The urban place-maker Jay Pitter adds:

Many communities that have been historically excluded do not come to the table with the same levels of spatial entitlement. And so, when you're saying you're ‘co-creating’ with them, you have to consider that you’ve come to the table with a different level of entitlement and authorship power. How does this power imbalance get accounted for?

“It’s not just getting people in the room. It’s giving them equal voice,” said Richard Perez, of the Sundance Institute.

Some interviewees worried that the word co-creation is outdated, tethered to old ideas of creation and originality, in a culture that is now really all remix. Yet others are concerned with the opposite, that co-creation needs to directly address ownership of story head-on: who gets to tell the story, why it is being told, and who gets paid and credited for the story. Co-creation is not a license to steal, like some swarm of locusts stripping a field. “There are cowboys out there,” said Heather Croall of the Adelaide Fringe Festival, “who have sort of decided this language is cool, but they don't care about the deep change. They don't care about the deep thinking.”

“I used to love the term co-creation,” said noted Italian researcher, Paolo Provero:

until I saw two years ago that, Creative Europe, the funding scheme of the European Union, was baptized as “co-creation.” It has been institutionalized, so removed from a bottom-up perspective, and it’s actually become a [top-down] vertical.

Amazon Mechanical Turks are named after the Mechanical Turk or Automaton Chess Player, a fake chess-playing machine constructed in the late 18th century. The contemporary Mechanical Turks work as freelancers to perform tasks instead of computers, often in small amounts of piecework, negotiated on crowdsourcing web-services system owned by Amazon. Karl Gottlieb von Windisch - Copper engraving from the book: “Karl Gottlieb von Windisch, Briefe über den Schachspieler des Hrn. von Kempelen, nebst drei Kupferstichen die diese berühmte Maschine vorstellen”, 1783.

There is reason to be suspicious at the way co-creation has come into vogue as a concept, one that coincides with dramatic shifts in digital-age economics. “Here comes everybody,” was internet advocate Clay Shirky’s famous phrase (borrowed from James Joyce) used to describe millions organizing in flat, decentralized networks online. But now perhaps we’ve reached another stage; there goes everybody, into the new share economy. Through Uber, Mechanical Turk, Facebook, and fandoms, millions of people are lending their ideas, content, and labor to highly centralized profiteers. It is crowd-fleecing rather than crowd-sourcing, as Trebor Scholz of the Platform Co-op Network put it:

Online labor brokerages enable wage theft, discrimination, and exploitation. According to the Network’s research, currently one in three Americans is a freelancer, and by 2020, 40 percent of the U.S. workforce will be. Independent contractors lose their rights guaranteed under the Fair Labor Standards Act, and they are not covered by unemployment insurance.2

“The problem is that these people, because they are so dispersed, they don't really have the opportunities to unionize the way that workers in factories had,” said Agnieszka Kurant, who explores collective intelligence in her art with systems such as termites, slime mold, and Mechanical Turkers, (who work as freelancers to perform tasks, often in small amounts of piecework, negotiated on crowdsourcing web-services system owned by Amazon). She stated:

These platforms, like Amazon, are preventing unionizing tendencies and they punish or exclude workers who are protesting the company. There are forums like Turker Nation and places where the [Turkers] discuss this, but then the platforms strike back.

As the term co-creation circulates into popular usage, it could fall victim to shiny-new-word syndrome and get trapped in the rapid cycle of co-optation, like gentrification; co-creation could be sucked up into the vortex of digital empires. Tabitha Jackson recalled how the word empathy, for instance, has fallen into misuse, with virtual reality being described an “empathy machine”. She said: “No, it isn’t! You have to really think what empathy means and think what VR is doing and decide whether or not they are the same. And I just don't want co-creation to become one of those terms.”

In 2015, Chris Milk called Virtual Reality an "empathy machine" in a ted talk. The description became hotly debated. Above: an early virtual reality system called the Sensorama.

The risks are plentiful, and co-creation, if misused, can stir up a hornets’ nest.

Fortunately, co-creation includes a constellation of methodologies that prevent those dangers. Often, while slower, these methods are ethically more robust than conventional ones. While we want to focus on quality media products, the importance of process is one of the things that really differentiates co-creation, particularly through who does what, when, how, and why. These methods are the toolkits, the frameworks, or mechanics, that actually help mitigate the issues outlined in the previous part, and that restore balance. Co-creation requires intentional consideration to re-invent the rules, because co-creators work in areas outside of and sometimes against convention. “The idea of co-creation, collaboration, equal partners, that's not something you learn in school,” said Julia Kumari Drapkin of ISeeChange. She added: “Not [at] the journalism school I went to.”

ISeeChange is a platform and global community that uses co-creative and cross-disciplinary methods between journalists, scientists, on-the-ground community members and now, with NASA, to monitor and understand the socio-environmental impacts of weather and climate change.

Importantly, the following suggestions are not a to-do list, nor are they prescriptive formulae. Rather, these are areas of consideration and practices that have worked in specific contexts. They are cited to help begin discussions and consider adaptations to local and unique situations. “The toolkit phenomenon is not new,” Bangalore community organizer and facilitator, Vishwanath ( Zenrainman ), said in a conversation with Babitha George. He stated: “But one has to also consider societal aspects here […] There are no generic solutions. There has to be localization of knowledge, inputs and experience.”

Fred Turner, who famously connected Whole Earth Catalogue counterculture with cyber culture, worries about what a limited prescriptive toolkit format implies:

To the extent that we imagine the politics take place in the intimate realm of personal power, we’re going to get lost. We’re going to keep building interfaces that allow for expression, that allow for the extension of intimate personal power, and we’re going to precisely not do the work, the boring, tedious, structural work of building and sustaining institutions that allow for the negotiation of resource exchange across groups that may not like each other’s expressions at all. So we have inherited from the Whole Earth Catalog a language of individuals, tools, and communities, which we’ve translated, I think, in tech speak, into individuals, communities, and networks. I would like to see a language of institutions, resources, and negotiation take its place.3

The following lessons summarize our findings.

How do co-creative projects begin? A conventional feature film, art exhibit, or public-service campaign will have predefined outcomes, and the makers will seek out relationships, crew, subjects , technologies, resources, and methods to serve the goal. Instead, co-creative projects begin with relationship. These projects start by creating a space wherein people may gather and ask questions. There may be a complex problem, or set of problems, that people want to address. Eventually there will be outcomes, often many, but these emerge out of the process rather than the other way around. Co-creative relationships begin by listening.

“Quipu Project” is an interactive documentary co-created with local community organizations and indigenous Peruvian women to document stories of forced sterilization under Peruvian President Alberto Fujimori in the 1990s. The result is a participatory oral-history project that culminates in a call to action. For the survivors, sharing their stories also might double as practice for future court testimony, serving in their current fight for justice. Photo courtesy of María Court and Rosemarie Lerner.

“Pathways to participation” is how the filmmaker Michael Premo describes this early stage of process at Storyline, his organization with Rachel Falcone. He reported:

We convene open meetings by reaching out to groups, organizations, friends, colleagues, people we admire. Sometimes those conversations are one-on-one, so we'll just talk to people directly and be like, “So, what's happening? What are you up to? What campaigns and things that you look at in the next 12 to 18 months?”

Michael Premo and Rachel Falcone co-created “Sandy Storyline” as an interactive and participatory web documentary about the 2012 hurricane that devasted many communities on the east coast of the US. Photo courtesy “Sandy Storyline”.

Most co-creators identify deep listening and dialogue as the key first step, and continued steps, in the process of developing a joint and equitable project design. As Gloria Steinem wrote about listening: “One of the simplest paths to deep change is for the less powerful to speak as much as they listen and for the more powerful to listen as much as they speak.”4

Many veterans of co-creation equate the process with a loss of ego, accompanied by a good dose of humility. Judy Kibinge co-created Docubox, an organization dedicated to serving the documentary community in East Africa. She said:

I think it begins with recognizing that you really don't know anything. […] You don't know anything at all. And so, you create a program and you try to be very receptive to the needs of the people that you created the program for.

Vincent Carelli, of Vídeo nas Aldeias in Brazil, described their work as "counter-methodology”. Courtesy of Vídeo nas Aldeias.

Vincent Carelli, of Video nas Aldeias in Brazil, described this as "counter-methodology […] It’s about going to people’s houses, building bridges, and lots of listening. It’s not a technical thing. It’s about discussions that are not imposed. So the most important thing is the dialogue.”

In his research for an upcoming book on designing dialogue, Fred Dust of IDEO is spending time at Quaker meeting houses to learn about consensus. “Quakers believe that decisions will come out of the silence of listening, and it's a collective process,” he said. “It's not exactly storytelling, but it is an act of co-creation.”

Due to the hazards of exploitation and hierarchy, Jay Pitter acknowledged that “narrative risk” in her process, and stated:

One of the ways that social imbalances manifest is that historically marginalized people are often required to share delicate parts of their stories, often rendering them more vulnerable. Individuals with more social power tend to perform their stories with omissions that protect their social status and power. We rarely explore the inner-worlds of individuals from socially powerful groups; they are usually the ones of the safe side of the storytelling process. I always say, as a starting point, that you actually don't have a right to ask a question … that you wouldn't answer yourself.

The first chapters of co-creation may be open, but not completely without structure, or facilitation. The process is a continuum, said Ethan Zuckerman, director of MIT’s Center for Civic Media:

There’s the orthodox method, where you really start with that blank sheet of paper. But then, particularly around technologies, which can sometimes bring capabilities to the table that are non-obvious, I think where we're starting to end up is iteration. Where we are putting out that sacrificial technology, building a community, contemplating what might happen around it and then iterating and maybe changing who's at the table, maybe changing what the prompts are.

Michael Premo identified such prompts as “handrails” to help give a framework to the discussion, rather than leaving it completely open-ended.

One group has developed a toolkit specifically to help guide how human rights defenders and affected communities might work together. Engage Media and members of members of the Video for Change network have published the 2019 Impact Pathway: A Video for Change Toolkit.

Some co-creative teams have created decks of playing cards with prompts that offer non-linear stimulation for dialogue and that may help to shape conversations. Iyepo Repository created a deck of these cards because “[they] realized there needs to be some scaffolding,” said Salome Asega. She commented:

It is actually impossible to just get people to think about the future without directions. So the cards provide prompts and scaffolding — the conversation can go anywhere, but we need the things to ground you, to give you a starting place.

Iyepo Repository created a deck of playing cards to use during participatory media workshops.

And Jessica Clark of Dot Connector Studios created a deck of cards she uses to inspire ideas for media-impact strategies, specifically for funders and journalists. “There’s no one linear path — it’s a mix-and-match moment,” she explained.

Listening does not end after the first meeting of a co-creative team, it requires a serious commitment on the part of the team to iteration and agreeing that things will change along the way. Too often, members of projects stop the listening portion of the project after the first round, and later, the approach is reduced to a one-time consultation, or even data-mining by those in control. But that is where the problems set in, and co-creation ends. In authentic co-creation, these initial steps are only the first term-setting conversations, and not the last.

Vertov’s Kino-Eye collective made one. So did the hackers, and the “Mundane Afrofuturists.” Manifestos are declarations of the ethics, principles, and values of groups that push new ideas. Many of the co-creators, collectives, and media movements in this study have assembled similar lists of principles. Allied Media Projects, Data for Democracy, and Platform Cooperativism are only a few of the dozens of organizations that have published sets of common values that define and guide their work. Design Justice Network goes further to document and make the processes transparent, that is, those used to make their list. They do this through publishing their elaborate ideation session as well as a wiki version.

The Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov was the founder of the Kino-Eye filmmakers group, who penned one of the earliest cinema manifestos. Film still from Vertov's “Man with a Movie Camera”, 1929.

In 2005 Katerina Cizek and her co-creators drew up a manifesto in the early years of the hospital-based, Filmmaker-in-Residence project (NFB of Canada). This was a first step in the project, and was largely used as a tool for communicating with potential partners and co-creators who often assumed that the team simply wanted to make films about them. The manifesto spelled out a different intention: to work with health-care workers, as well as communities, in a joint process of discovery rather than documenting what they already knew. Later, the NFB created a short film based on the manifesto and used it to describe these principles to audiences. Cizek and the team adapted a similar manifesto for HIGHRISE (2009) that outlined the common principles shared by their many co-creators: architects, residents, government, technologists, and artists. Based on those two manifestos, they are developing a manifesto for the Co-Creation Studio at the MIT Open Documentary Lab, and have adapted it through discussions with focus groups.

Helen Haig-Brown and Gwaai Edenshaw co-directed “Edge of the Knife” through a community-led process, incorporating community members and elders in the writing/translation and working with existing Haida governance structures. The film was an act of language preservation, in which participants were able to expand their knowledge and fluency in the Haida language through work with elders, as well as share the language within their community. On the set of “SGaaway K'uuna” (“Edge of the Knife”). Photo credit فرح نوش Farah Nosh. Copyright Isuma Distribution International.

For the Edge of the Knife (2018), the Haida film project (see: Spotlight, in Part 3), the first thing the makers did was draw up a list of goals and values. They ranked these and found that the highest priority item was authenticity; this gave the group an imperative to represent Haida culture authentically, and always in close consultation with elders and knowledge-holders. Jonathan Frantz, the producer and cinematographer stated:

Then further down the list were more conventional things, like make a film that has high production value or relating or might have a chance to make it in a film festival. […] Any time we had any roadblock or stumbling block with decision making, we would go back to our set of values and use that to help us make a decision on which way to go.

Naming common values helps identify what matters most to group members and articulates their reasons for coming together.

(For sample manifestos, see Appendices).

This is the paperwork. While some co-creative teams never sign anything, many use negotiated documents up front as a way to articulate and agree on relationships, ownership claims, and ultimate benefits. The standard tools in film and media are the individual consent or personal release forms. Filmmakers ask subjects to sign forms that state the participant agrees to be in their films, and that they are releasing their image, words, and sounds, often in perpetuity, for all media, everywhere. In academic and medical research involving human subjects, this is known as individual informed consent, and acknowledges that the subject has a basic understanding of the research, that they consent to releasing their information and data, often with a guarantee of anonymity, and they have the right to opt out at any time. The inconsistent, troubled history of the use of these tools dates back to 1900, which is considered to be the first time informed consent forms were used in medical research, by the US Army, studying yellow fever.5

Some interdisciplinary-co-creative projects have attempted to reconcile the opposing guarantees of media releases and research consents. It is difficult to guarantee anonymity and a right to withdraw from a project when media is involved. In a digital era especially, images, text and sound, once captured, can be disseminated anywhere, with or without consent. Louis Massiah of Scribe Video Center challenges the standard that consent forms be signed before an interview, as most academic and broadcast protocols dictate:

It feels a little bit presumptuous, if not downright colonial and colonizing … I look at an interview as a gift, the witness/interviewee is sharing with the media maker, as opposed to selling something to be commodified. When you make a community media work, the people that are on camera or participating as subjects are doing it because they believe they are trying to support the goals of the project, and they also need to understand that the edited work is going to be in their own interest.

Used well these forms are an opportunity to conduct a deep dialogue between participants and co-researchers, and they offer a range of options that details the risks, responsibilities, and benefits for all involved. In the NFB Filmmaker-in-Residence program, for example, when working with a group called “Young Parents of No Fixed Address,” Cizek and her team created iterative and staged levels of informed consent with corresponding levels of anonymity and participation. The health-care based research coordinator developed the tools, and then spent hours discussing options with participants — often young people at risk of being harmed by going public with their stories. The team returned to these principles and options frequently as the projects developed.

In the NFB Filmmaker-in-Residence project (2006), when working with a group called “Young Parents of No Fixed Address,” Cizek and her team created iterative and staged levels of informed consent with corresponding levels of anonymity and participation.

In Dimensions in Testimony, Stephen Smith of the Shoah Foundation worked with Holocaust survivors in a new technology environment. He noted that it could be daunting, ethically, to:

[place] an 85-year-old individual into a 15-foot dome with 6,000 LED lights and 116 cameras, and ask them a thousand questions about their life over five days. Just seeing that, that would be an imposition and possibly dangerous for that individual to go through that experience.

“Dimensions in Testimony” lets viewers have conversations with Holocaust survivors and other witnesses to genocide through interactive recordings of interviews. This approach allows each viewer to create their own interview experience by directly asking the questions they have for survivors, receiving testimonies from the survivors, mediated through interactive techniques. Courtesy of the USC Shoah Foundation.

But Smith, who holds a PhD in testimony methodology, developed a complex protocol with his team, and with survivors who sat on an advisory board, to shape the process. They asked that family members, rather than psychologists or social workers, accompany all interviewees to act as advocates.

Many co-creators have also identified the need for instruments that help address inequities at a more systemic level, and guarantee rights and responsibilities to entire communities. In 2009, Screen Australia, a federal media agency, published an influential document called Pathways and Protocols: A Filmmaker’s Guide to Working with Indigenous People, Culture and Concepts. Therein, the Indigenous writer and lawyer, Terri Clarke, offers “advice about the ethical and legal issues involved in transferring Indigenous cultural material to the screen.” A similar document is now in development in Canada at the newly formed Indigenous Screen Office, together with the ImagineNative Film Festival and Institute.

Ellen Schneider of Active Voice has been developing customized tools called “Pre-Nups for Filmmakers.” For over a decade, she’s been working with funders, filmmakers, and nonprofits to navigate the increasingly complex nuances of co-creative partnerships that go beyond the mold of conventional filmmaking. “When I first started working on this, some people were concerned that even raising those what-ifs could be daunting and a deterrent,” said Schneider:

But the more that we dug into it and the more people gave us recurring feedback, people said, “Let’s just get it on the table, because if there's concerns about, you know, shifts or changes of plans that we have no control over, let's deal with it now.”

Schneider has broken down the process into four sequential stages: “mission, method, money, and mobility.” The big stumbling block can be money, followed by how the project will move in the world.

"Who's controlling what resources and how are they allocating them?" asked Sheila Leddy of the Fledgling Fund. She continued:

Many people think of accounting as just financial accounting, like your income statement and balance sheet. But there’s a broader understanding of management accounting that is very much about thinking about cost drivers and who has control over those, and how you're reporting on those, so that you can manage them, not just report out. So, what are the systems that are going to be in place and who's included in actually figuring out what that budget is?

How will decisions get made, and at what stages? Sasha Costanza-Chock, professor at MIT, said that this is key to a co-creative agreement: “Is it consensus? Who decides?” In the software world, Brett Gaylor of Mozilla noted that teams working on projects will specify “who is Responsible, Accountable, Consulted and Informed,” and the model is now used in digital agencies, and increasingly, in inter-disciplinary emerging technologies storytelling.

Meanwhile, cultural groups are exploring Cultural Community Benefits Agreements (CBAs), that spell out the terms of engagement, especially for outside organizations coming in to work with local groups. Indeed, Detroit Narrative Agency (DNA) asked the MIT Co-Creation Studio to negotiate an agreement around the terms of our mentorships and co-research for this report.

These cultural agreements pick up on the model of CBAs that have become common in urban contexts in recent decades, to negotiate terms for local communities when developers arrive to transform neighborhoods. These are legally binding instruments signed by developers, municipal governments, and community groups. The benefits at issue might include local jobs, living-wage requirements, affordable housing, and neighborhood improvements, according to the Parkdale People’s Economic Project.

These types of agreements date back even further in Canada’s north, specifically with the mining industry in the 1980s. There, they are known as Impact and Community Benefits Agreements (IBAs). However, critics warn that they can have an exploitative effect, for instance by compromising communities’ land claims. They are not public-policy documents, but confidential agreements subject to contract law, and often demand that communities relinquish the right to protest or even publicly criticize the companies in question.

CBAs have also been used during the amalgamation of the broadcast system in Canada. Ana Serrano, the director of the Canadian Film Centre notes that her organization profoundly benefited from this process, which mandated that a portion of broadcasters’ taxes went to community groups like hers. But the effects can be fragile. She told us:

[Throughout] my career at the film center, it was one of the big ways that cultural institutions got money. But, in the past five years, the community benefits were taken out of these deals. A good example of that is Netflix. They don't even pay tax [in Canada]. So, it's become unfashionable to demand that.

Consent forms, community-benefit agreements, and memoranda of understanding are not panaceas. Veterans of co-creation are acutely aware of their pitfalls and problems, but do use them to guarantee certain basic rights, alongside bigger policy and legislative concerns affecting the role of government; this includes how we define and use public space, the commons, and how we will govern ourselves and shared resources into the future.

By the Detroit Narrative Agency: excerpts from a group interview in which they discuss the importance of putting terms in writing before co-creative work begins.

ill Weaver of Detroit Narrative Agency (2018). Photo by Kashira Dowridge, courtesy of Co-Creation Studio.

ill Weaver: For DNA, when we first got approached by MIT to collaborate on this research process, we wanted to make sure that the process felt really equitable, not just to us, but more importantly, to the cohort members and any other community members that would interact with the process. For us, it felt really important that there was a set of clearly stated, not just principles and guidelines, but actual expectations around how the process will play out, to have some tangible ways that we can strive towards and measure how equitable the process would be. So then we invited the MIT team from Co-Creation Studio to join us in negotiating a working document that would be a cultural Community Benefits Agreement in the form of a memorandum of understanding between DNA and them.

paige watkins: […] I think that you run the risk of whatever is produced, if it's an event, if it's a conference, if it's a gathering of people, some kind of institutional partnership, I think you run the risk of spending all this time planning, and then the thing happens and it's not what you agreed to. Or they last-minute changed all this stuff around about it, and now all of a sudden it's out of value alignment. It could be exploitative to the community members, especially in Detroit, a place where more and more people are wanting to have conferences here, more and more people come here to do things, thinking that they can just kind of come in and do their thing and then leave without being accountable to anybody.

So I think you just run the risk of folks doing whatever the hell they want and not actually thinking about what the community needs or thinking about actually supporting folks from the community. You [could have] an event that was like a couple-hundred-thousand-dollar budget, you know what I mean, and all of these vendors are white folks from the suburbs or something like that. You just run the risk of things happening that are out of alignment or out of whack, and then having to backtrack and fix stuff rather than doing things in the beginning before anything's decided.

ill Weaver: And I'll just add to that, that you know I think even in the best-case scenario where people have similar values at institutions and they come in with really good intentions and all that, then like if they're not clearly articulated and you're not building that in as a structured formal part of the process, then you run the risk of your intentions falling through the cracks because the logistics end up trumping, and the economics end up trumping your politics or your values, you know what I mean? What's the thing Grace Lee Boggs would always say? “Politics in command.” It was a phrase that she used to say about how we end up running the risk of our politics falling to the wayside to make certain economic decisions or logistical compromises. Because there's systemic exclusion and divestment from our communities. So then, how do we proactively do that?

And that's on a money-spending level which is easier to track, but then I think we're also interested in the percentage of projects that get featured in an event or the background of the trainer that we collaborated with … I think to prioritize black and people of color filmmakers so we're not replicating this thing of outside-of-Detroit white people as the experts of this storytelling process. So these are all part of the equity piece. I think in other projects we've also looked at safeguarding against co-optation, and I think that's something that we really thoughtfully did together with MIT in our CBA with them: How do we make sure that DNA is listed as co-authors, and there’s input at every step of the process around content? And that's not to make any assumptions or accusations that things will go wrong, but it's just about, how do you build a process that gives you agency and space throughout the process to chime in if there's a red flag or a concern?

Morgan Willis: I think the last thing, what you all are also making really clear, is that community benefits agreements have the opportunity to invest in local work and local people who are doing work that allows their platform to grow. So it's also a way of tangibly investing in our local economy. Then folks who are here have an experience that is more reflective of the actual local community. They also have reference points of, "Oh my God, did you do this thing? Did you taste this person's catering?" or whatever. We get really excited about whoever the person is, or the place is, because it's gonna be something that they've not had before. Typically they've only relied on online searches to tell them what their nearest, whitest, or most resourced people who do this work are telling them to do.

(For a copy of the Community Benefits Agreement signed by DNA and MIT Co-Creation Studio, see Appendices)

Many co-creative projects directly challenge the industrialized, product-driven, commodified notion of media-making. However, there comes a time to discuss the media itself. Just how important is the quality of the media?

At Challenge for Change (NFB), 50 years ago, the program prided itself in being profoundly interested in process over product. This was radical for a film agency that had been, at that point for 30 years, at the vanguard of championing documentary and animation as legitimate art forms and industries. Although the Challenge for Change program ran for a decade, much of the resulting film material, thousands of hours, was never edited or synthesized, but was used in fragmentary ways for community engagement. Of course, some films were completed, notably the controversial The Things I Cannot Change (1967) which depicted its subject, an impoverished family, in an unflattering light . As a result, George Stoney, head of Challenge for Change at the time, wrote a harsh treatise on a new code of ethics for the program.

The NFB Challenge for Change collection notably included 27 films by Colin Low about life on Fogo Island, Newfoundland, produced in 1967. Photo courtesy National Film Board of Canada.

Colin Low, the director of the Challenge for Change Fogo Island project, recalls his debates about process versus product with John Grierson, the founder of the National Film Board of Canada, a mere three months before Grierson’s death in 1971. Over the course of three guest lectures in Grierson’s university classes, performing before students, the two battled out the value of the Fogo project, journalism, propaganda, and editorial style. Low recalled:

“What,” Dr. Grierson wanted to know, “was the value of the film off Fogo Island? Was it good for television? Mass media? What did it say to Canada? […] Why would the Canadian taxpayer allow such an indulgence?”6

Low was devastated by Grierson’s exasperation with Challenge for Change. Grierson was craving drama, while Low had thought he was fulfilling Grierson’s own call to make “peace more exciting than war.” Thirty years after this debate, the NFB sought to revive Challenge for Change, but this time aligning process with product. When Katerina Cizek and a cohort of filmmakers were invited to reinvent the program in the digital era, her producers, Peter Starr and then Gerry Flahive, attempted to embrace the ethos of Grierson and Low. They asked that Cizek put process first, and to add layers that would create media that would transcend the communities it first served, and speak to broader audiences. Initially, the NFB wanted a feature film about the process, which Cizek worried was too laborious and intrusive, but then the team went on to consider the web, and to co-create the world’s first online feature-length documentary for global audiences. Along the way, they decided to produce multiple products that would serve different needs. Short, rapid community-facing outputs such as teaching tools, short videos, newsletters, flyers, etc., were sometimes more important to community partners than the high-quality media product intended for wider audiences.

For many groups in this century, both the quality of the process and the quality of the production are crucial. For decades, community-based media work has been relegated to low-quality aesthetics and unrefined narrative structures, but today, when media tools are more accessible and high-quality visuals and narratives are ubiquitous, co-creators also see the need to create attractive and engrossing products. As paige watkins of DNA commented, during a group discussion:

If you want the product to actually have impact past the choir, past the people who already understand what we're talking about and are agreeing with our values […] it has to be competitive up against the harmful things that are getting maybe more money or more resources.

“Projects emerge from the process,” is how Heather Croall, director of the Adelaide Fringe Festival, succinctly explained co-creation in the 21st century. For most co-creative teams, it’s not one or the other. Product and process are complementary.

When projects are born from co-creative processes they often flower into diverse, alternative forms of narrative structures. Co-creators can shed linear, conventional formats (such as three-act structures), and embrace non-linear, open-ended, ongoing, multi-vocal, and circular, spiral forms. These of course, complicate the question of quality, which can imply not only traditional aesthetic norms, but innovation. “There’s potential, for the form itself, that co-creation can result in an expansion of the language of non-fiction,” said Tabitha Jackson of the Sundance Institute.

“Rather than deductive argument or grand narratives, these projects employ mosaic structures of multiple perspectives,” wrote Patricia Zimmermann and Helen de Michiel in Open Space New Media Documentary: A Toolkit for Theory and Practice (2018), “Open space new media documentaries explore the terrain where technologies meet places and people in new and unpredictable ways, carving out spaces for dialogue, history, and action.”7 (For more, see In Conversation: Decentralized Storytelling, in Lesson 5 )

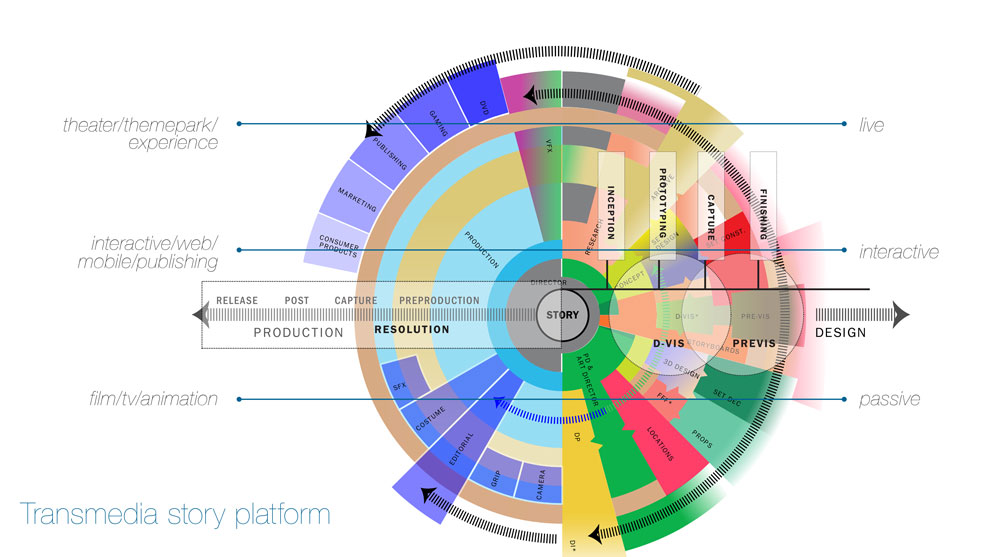

World Building Institute illustrates the complex iteritive process of creating storyworlds.

Graphic from worldbuilding.usc.edu

Complex narrative world-building and story-universe labs proliferate in the science-fiction and speculative-media space. Alex McDowell’s World-building Lab at the University of Santa Cruz and Lance Weiler’s Digital Storytelling Lab at Columbia University School of the Arts both co-design spaces with and for participants to imagine future worlds. McDowell’s worldbuilding philosophy, for example, designates a narrative practice in which the design of a world precedes the telling of a story.

“Sherlock Holmes and the Internet of Things” is a Massively Offline/Onlince Collaboration (MOOC). Participating teams adapted objects from Sherlock Holmes stories to create storytelling objects that were plugged into a global, connected crime scene through Internet of Things technology. Courtesy of Columbia University School of the Arts’ Digital Storytelling Lab.

While science fiction and documentary non-fiction might at first seem worlds away from each other, they can co-exist, especially in a co-creative cosmos. Cinema Politica in Montreal is championing a new genre, Documentary Futurism. This genre, according to Svetla Turnin and Ezra Winton on their website:

could be described as the creative treatment of actuality and the documented actuality of fantasy. This new genre traces a kind of filmmaking that subverts audience expectations of the real and maps on to depictions of social reality an expressive speculation of what could be or what could be imagined.

The team launched this via a call for submissions for a collection of the genre’s first short films.

Open narrative forms can be deeply connected to re-imagining civic engagement. In For Freedoms (2018), Hank Willis Thomas is making a direct connection between art and civic life by creating town halls and large public art projects in each of the 50 states. He told us:

Everyone has something to say and something valuable and something important or interesting. It's just about what best suits them. The more people, I think, are invested in making space, new stories and new ways of telling stories, the better off we all are.

Henry Jenkin’s Civic Imagination Project scales this approach as an ongoing action and research agenda at the University of Southern California, that is based on eight years of research. The project taps into the speculative capacities of citizens at the local level, bringing together and bridging the perceived gaps between different stakeholders, especially youth. The team conducts research, ethnographies, and runs workshops across the country to seed trust, and new imagined civic futures.

Excerpt from a conversation with Amelia Winger-Bearskin, artist and curator.

Amelia Winger-Bearskin: We [Indigenous peoples] have our own traditions and I just want to make sure we're able to speak about them, learn about them through the context that we give them. And I'm certainly someone that believes in sharing our culture and having other people participate with it, but also, I want to make room for us to have our chance to say what we want to say about our culture and then also contribute to other research.

One of the main concepts I've been working with is decentralized storytelling. I’m charting the history of the type of storytelling that I'm seeing, that's most popular among younger millennials, that's created through different online platforms […] They take the form of VR Chat and Rec-Room and Alt-Space and indie games and ROBLOX and Minecraft, and I can go on and on and on. It’s [for] ages from 10 to maybe 25 and they are telling longform, complex narratives from hundreds of people's perspectives that are all participating in a story. And that is a more similar corollary to the way in which the Iroquois would tell stories.

The Iroquois with Six Nations spanned a massive amount of area in the northeast. They had trade routes all the way down to Chile and beyond. So in order to share the technological advancements that they made as well as the spiritual lessons that they were learning from different communities, they would do it in the form of story. The stories were very longform. They would use a multiplicity of different types of tools: pottery, baskets, rock formations, natural land monuments — as both mnemonic devices, to remember details about them, as well as to share those with other groups of people.

These were very complex and long stories — [it] would take a week to tell the section of the story that you're trying to convey. It was entertaining, it was community building, it shared values, but it also shared technological advances from one community to the other, by connecting to a story that people were familiar with. It gave a wider chance of being remembered and being relayed.

For instance, we still make cornhusk dolls. The cornhusk doll story is a way of teaching a specific type of planting process and harvesting process. And the Iroquois farmers taught Benjamin Franklin how to farm, and taught him about decentralized systems of democracy, and a model for how agriculture was created within the United States. And so ... the reason you use a doll to tell a story is that a child learns and remembers, and you have a longer chance of having that community remember the story. If someone learned that story when they were five and they remember the story when they were six and kept hearing the story as they grew up and they begin to plant, they remember this technological [lesson].

Corn Husk Doll. Photograph by John Morgan, distributed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License

So that's just an example of how stories were distributed across hundreds of people. They also had different formats of story. It was a doll, it was something that someone would say, it was a song. [...] And it was also a time of year. And that, to me, seems more similar to the way in which the younger generation is telling their stories, through these distributed experiences.

Safety first. What does it mean to prioritize the well-being of the people involved in co-creation projects? It means moving projects and participants towards healing and also thinking profoundly about the sustainability of the project, by protecting its participants, and building and leaving renewable resources within the community. Bringing people into co-creative processes can make them vulnerable, whether in person or online. Brett Gaylor of Mozilla said:

Bringing people in, they're not necessarily in our toolkit. Having concrete methodologies to do that, I think, can be really transformational, and it also protects the safety of everyone involved, and I think that's a real critical thing that's needed in the field.

As part of her media-impact card deck, Jessica Clark advocates for a safe space engagement model. This is predicated on the idea that “people's stories are valuable, that people need a place to talk where they're not going to be judged, and watched.”

Too often, the most vulnerable actors are the ones working independently at the local level. As of July, 2018, 1,312 journalists have been killed worldwide since 1992, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists; many other kinds of activists are also under threat. Along with the work Witness does in helping people produce and safeguard video evidence of human-rights abuses, program director Sam Gregory is exploring the idea of “co-presence,” which involves live streaming well-informed witnesses from remote locations into crisis areas, such as protests and stand-offs. He contends:

Witnessing implies the obligation to watch and to act. What is it we can do that involves bringing people into live stream that makes them active agents in the narrative as it goes on, driven by the needs of the front line activists? Not to tell people on the front lines what to do, but to do things that could change events by the support … for example, by translating, or adding context, or sharing it rapidly. Or can they provide specific skills, for example, a legal observer?

Many communities involved in co-creation have experienced oppression and trauma. Unfortunately, the very process of co-creation can expose, re-open, and even create wounds. How then do teams not only mitigate trauma, but actively contribute to reconciliation and collective health?

Focussed on healing, re-entry and sustainability, the People's Paper Coop "is an ongoing initiative by the Village of Arts and Humanities that connects formerly incarcerated individuals together with artists, civil rights lawyers, and many others to run a multitude of programs and initiatives. Through a highly collaborative and multidisciplinary process, the PPC and an incredible array of city-wide partners, work with individuals directly impacted by the criminal justice system to develop the tools, skills, and networks to advocate for themselves, their families, and residents across the city. " Courtesy of The People's Paper Co-Op.

At Standing Rock, when Algonquin/Métis filmmaker Michelle Latimer bore witness with her camera she also participated in regular ceremonies with elders on site. She stated:

That was something I had never done before, actively engaging in a ceremony in a really regular way. But it was such a difficult period of time for me personally, just being in that kind of war zone, seeing what was happening to the people. […] It was just so emotionally draining that I felt that engaging in that ceremony every week with those same people was incredibly cathartic, and it really gelled and solidified a collective idea of … what we were trying to achieve together, not only as storytellers but as political activists and people who are part of a movement and occupation.

Healing also involves sustainable development of a project and communities. Further, many co-creative projects are interested in creating renewable economic resources for communities. The Fireflies: A Brownsville Story project in Brooklyn is not only a documentary VR game, but will be used as a peace-building process that allows residents to virtually cross territories normally off-limits to them. The Brownsville Community Justice Center and Peoples Culture plan to install the game in the lobbies of more than 14 public housing buildings, to nurture conversations about how to heal the fractures in the community. The project maintains the Brownsville Tech Lab in order to train youth in game design, coding, and other crafts of media-making. As producer Sarah Bassett said, they “want this game to live in the world — but at the end of the day, it's made by and for the community, with the purpose of [being] shown and played in the community.”

“Fireflies: A Brownsville story” is a community-based documentary VR game created by and for the residents of Brownville, a neighborhood in Brooklyn marked by an ongoing rivalry between public housing developments. In the game, players from both sides of the conflict work together to explore the histories and dreams of the community and its residents, searching for the commonalities amongst the conflicts. The game is developed by the Brownsville Community Justice Center and the Peoples Culture collective who plan to install it in the lobbies of more than 14 public housing buildings, to nurture conversation about how to heal fractures in the community, and maintains the Brownsville Tech Lab to train youth in game design, coding, and other crafts of media-making.

Co-creation allows for, and demands, appropriate forms of leadership, language and technology.

In the 21st century, conventional notions of employment and jobs are transforming in a massive, business-driven paradigm switch. Sheila Leddy of Fledgling Fund has worked with filmmakers to help them adapt to changing systems:

When Fledgling first started doing this work, the business models were changing, and expectations were changing. There was push back about impact. “What do you mean I have to care about impact? What do you mean I have to measure this? I tell stories, I'm a filmmaker.” […] But I think storytellers need to be part of the conversation and to participate in the development of new models, or you're going to get run over by the business people.

What do the new models of leadership look like with a mindful, intentional approach to creating new spaces for co-creative models? In flattening and shifting power dynamics, co-creators learn to respect expertise in non-hierarchical systems. In non-fiction media, this means that the people formerly known as directors and producers take on new roles. We asked in our interviews and group sessions what these new roles could be called (see illustration below).

“There’s a certain conception of what a leader is: the lone figure. It's like Gandhi, right?” said Lina Srivastava, of Creative Impact and Engagement Lab:

[He] was indeed one kind of a leader, he did lead a national resistance movement, but there was an entire mechanism that was working alongside him. He did nothing alone. Take the Salt March, for example. The movement was a very strategic movement. There were multiple parts, and it was leaderful. I hate that word, but it was leaderful, and collaborative. It’s the kind of leadership that catalyzes transformational change in communities and in societies. So the important questions for me are: How do you apply leadership process to any particular social, cultural, political context? What are people and communities doing together, collectively? The answers are all based in stories.

Srivastava founded the Transformational Change Leadership project to document and communicate those stories.

“I've been a part of lots of different communities,” said Eleanor Whitley of the pioneering immersive story studio, Marshmallow Laser Feast. She continued:

Intentional communities where these kinds of leaders suddenly go, “I don't want to do this anymore. It's too heavy and it's too difficult and it's all of you have to decide,” and you're like, “No, actually you do need to — however you design what that community looks like — to create a path and to guide people down.” Leaderless teams fail.

Leaders might also consider themselves more instigators than primary producers. In projects such as It Gets Better or the Candles 4 Rwanda campaign, it was a matter of creating a template that a wide range of other media-makers, professional and amateur alike, could fill in with their own video messages, and providing a platform to disseminate these varied voices. “Co-creation … is a means to giving people what they need,” said Jennifer MacArthur. “And sometimes what people need is less power, to give them more of a sense of their humanity. And it's hard to know that, and it's hard to accept that in a culture that is obsessed with ‘bigger is better’.”

For Wendy Levy, Director of The Alliance for Media Arts + Culture , inter-generational collaborations in particular can suffer from a lack of relinquished power. She said “‘Youth media’ and youth makers are often marginalized, excluded or denied access to decision-making in supposedly co-creative environments.” Levy suggests that creating shared language, understanding creative leadership models and developing custom methodologies for specific projects can challenge structural inequities and help decentralized leadership.

Language can unite and it can exclude. In co-creative processes, when people from all walks of life come together to listen, engage in dialogue, invent and produce, language can quickly get in the way, and reproduce hierarchies in groups. “Talk normal,” said Fred Dust, author and former partner at IDEO. He continued:

Which seems easy, but it's not. We as designers, we as filmmakers, we as other kinds of practitioners, we learn special language and that actually can be highly exclusive language. So learning to just talk normal is really foundational to actually being a co-creative body and actor.

Heather Croall, former head of Crossover Labs and director of Adelaide Fringe Festival, told us:

You learn a shared language that when you've got people from different sectors, and everyone knows, everyone talks in a very different language, so coders talk in a very different language to games designers, to filmmakers, to scientists, to artists. You realize that most people walk in the room with their arms crossed and they're not really all that open to talking with each other. And then by the end they're really into it.

Some co-creative teams develop glossaries of terms and catalogs for their time together, to develop both mutual understanding and an efficient shorthand. Finding a common language is key to co-creation.

“Quipu Project” (2015). Courtesy of María Court and Rosemarie Lerner.

New technologies are exciting, and uncharted territories allow for co-creation to flourish. “You're not in a templated medium, when you're building something new. You absolutely have to work with people from all kinds of disciplines and totally different disciplines and it's kind of imperative,” said Liz Rosenthal, of the London-based film and media consultancy, Power to the Pixel, and co-curator of the Venice Film Festival’s VR Island. “Most of the time, though, the first wave of technology doesn’t get to artists and those pursuing social justice,” said Gerry Flahive, a former National Film Board producer and now a consultant to the MaRS innovation laboratory in Toronto. He stated:

I hope, in this sort of revolution, people who want to be involved in co-creation of socially engaged documentary could get just as ready access to those kinds of tools that are, obviously, already being used for tracking us, for understanding how we behave, by corporations and governments […] You can swim in waves of data and patterns that might emerge, and be playful with it.

As well, new technologies can be inaccessible to participants or potential audiences , and may actually get in the way of production. When projects get overrun by the technology, they run the risk of becoming solutions looking for problems. In her book, Twitter and Tear Gas (2017), Zeynep Tufekci documented how activists around the world have effectively used networked tools like text messaging, Twitter, Google spreadsheets and more, to strategically organize movements and tactically save lives. However, she wrote:

I have also seen movement after movement falter because of a lack of organizational depth and experience, of tools or culture for collective decision making, and strategic, long-term action. Somewhat paradoxically the capabilities that fueled their organizing prowess sometimes also set the stage for what later tripped them up, especially when they were unable to engage in the tactical and decision-making maneuvers all movements must master to survive.8

Fireworks — and cell phones — light up the night at Tahrir Square as demonstrators celebrate the resignation of Egyptian President Mubarak on Feb 11, 2011. Zeynep Tufekci documents in her book, “Twitter and Tear Gas” (2017), the successes and failures of online connectivity in people's movements around the world. Photograph by Jonathan Rashad, Tahrir Square on February11, distributed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Many co-creative teams that we interviewed argue for site- and culture-appropriate technologies for the making of decentralized, organizing work. In the Quipu Project, teams used analog phone systems to organize and share anonymous stories amongst Indigenous communities in remote parts of Peru. Vojo, the phone system developed in part at the MIT Center for Civic Media, also has been used to organize and share stories amongst immigrant laborers in California, to minimize the risk of exposing identities. “It is a privilege of those of us in [high income] countries [to] have endless access to electricity and to every kind of device imaginable,” said Patricia Zimmermann in our interview. “I actually think we have to think more like Malcolm X about this, and say, ‘By any technology necessary’.”

Photographs courtesy of María Court and Rosemarie Lerner from the “Quipu Project”.

Providing community access to technologies is core to many co-creative methodologies. Many 20th-century co-creation projects handed over radio stations, video cameras, and editing systems to communities. When the web arrived, with it came the digital divide; coding workshops and other ways of providing access to software and hardware popped up as a means of narrowing this divide. Now, with emerging and immersive tech, even greater challenges emerge.

NOVAC (New Orleans Video Access Center)

Iyepo Repository is a project that has emergent technologies to build media literacy and community training at its core. Salome Asega, one of the co-creators, noted that the learning curve for emerging tech is steep: “You can't just ask people to jump into making unless you're ready to provide a 101, a training of some sort.”

Iyepo Repository runs community workshops to develop projects (2017).

Iyepo workshops have gone through many iterations, from an idea-generating workshop to more hands-on opportunities with digital tools. They now offer a physical-computing track with Arduino , an open-source prototyping (testing) platform, and a VR drawing track with Vive and Tilt Brush, so that participants can draw artifacts in 3D space. There is also a digital fabrication track that includes 3D printing or laser cutting. “I can't make things with people using new technologies unless they also understand what's happening,” Asega said, “I have to make it feel like it's not magic.”

Some artists in this field split their own artistic and community practices, and consider them two different modes of expression. But they see the community-facing work as fundamental to their roles. Jason Lewis and Skawennati, for example, run their own studio practice, producing Indigenous machimas in the Aboriginal Cyberspace Territories . Concurrently, they run SKINS, youth workshops in gaming, coding and digital-story creation in the Indigenous communities in Kahnawake (on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec), and now in Hawaii.

Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTeC) started in 2005, and is a network of academics, artists, and technologists whose goal is to define and share conceptual and practical tools that will allow them to create new, Indigenous-determined territories within the web, online games, and virtual environments of cyberspace. Efforts include a storytelling series, an ongoing games night, a modding workshop, Machinima, and performance art with the objective of identifying and implementing methods by which Indigenous peoples can use new media technologies to celebrate their cultures. It was co-founded by Jason Edward Lewis and Skawennati.

One arm of Tahir Hemphill’s multi-functional studio in New York City involves a monumental archive of rap music, along with other research and art involving AI, software, and social justice. But he is also committed to a strong community-engagement practice. According to his website:

… public-programming methodologies that invite participants to engage critically with cultural research, data collection, data ethics, implicit bias, data bias, and storytelling — elements that ultimately empower the critical thinking and decision making that leads one to become more capable of establishing informed positions.

Community-based, co-creative, artistic interventions are crucial to mitigate these expanding divisions. There is a need to raise media and tech literacy, and even infiltrate the systems of production to inform how the tech itself can be built.

The following is an excerpt from our interview with Louis Massiah, director of Scribe.

Scribe Video Center provides filmmaker workshops, a free documentary program for community groups, and youth programs to promote video and film as tools for community support and self-expression. Scribe Video Center also runs programming around collaborative local histories, empowering communities to use research and oral history methods to explore their own neighborhoods and create a rich picture of their own history.

Scribe Video Center in Philadelphia is one of the longest running independent video centers in the USA. It began workshop programs in 1982, and pioneered co-creative programs through training and literacy with the emerging technology of the time, analog u-matic video. Recently, 44 short videos from the Scribe Centre project were selected to represent the United States at the new Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar, Senegal. We asked Massiah about the inspirations for this world-renowned center.

Louis Massiah: Often times, a confluence of impulses and inspirations may get things started, but it is the reality of material circumstance that has a huge impact on shaping things. In the 1980s there were a number of organizations, institutions, nationally, where people could come together and learn from each other and have access to equipment. We’re talking about analog video and 16 mm film, but we're also talking about technologies that were quite expensive and not that accessible. There weren't a lot of cameras and editing equipment floating around. And there certainly weren’t a lot of places where the expertise and the knowledge of the craft of filmmaking could be shared. And, as importantly, locations that supported the comradery of media creation. Aside from learning the craft, cameras and production equipment were heavy, so you needed help carting equipment around.

I was in a graduate program at MIT beginning in 1979. So it was immediately after leaving MIT in 1982 that I started Scribe. At MIT, I was in the Film/Video section, which was largely a purist documentary film program, that is 16 mm film (photo-chemical) production from the cameras to flatbed editing, which was led by Ed Pincus and Ricky Leacock. Although there were also folks in the program that were knowledgeable about the emerging video (photo-magnetic) technology, in particular Benjamin Bergery.

Prior to coming to MIT, I had worked at WNET in New York. While I was there, there was a sub-entity of Channel 13 called The Television Lab, with guests artists like Nam June Paik, Phillip and Gunilla Mallory Jones, Joan Jonas, Bill Viola, Alan and Susan Raymond and Shirley Clarke. The roster of video makers included some of the most noted artists of that time. David Loxston and Carol Brandenburg were running the TV Lab and John Godfrey was the technology guru. I have very clear memories of watching Paik edit at the TV Lab’s 46th Street studio, when he'd just gotten back from Guadalcanal. Also, around that same time I would go to paradigm-shifting video screenings at the Kitchen and the Museum of Modern Art [MoMA]. Deirdre Boyle had programmed a pretty extraordinary series of video exhibitions at MoMA.

I was in my early twenties and was learning about video as an art form. And also, appreciating the particular aesthetics that were involved with video. Video to me seemed closer to the capturing of truth and reality than 16mm film. So, I was embracing video.

My initial reason to go to the MIT Film/Video section was on a quest to develop a visual language to look at ideas in science. I was thinking, “Okay, MIT should be the place to do this,” but when I arrived, I realized that an exploration of video linguistics wasn't part of the intellectual flow nor the interest of the Film/Video section, which was almost exclusively focused on cinéma vérité documentary storytelling. And also 16mm film.

But I still wanted to work with video. I found this place in Boston at that time called BFVA, Boston Film Video Association, which allowed members to borrow equipment and shoot. So, the works I did at MIT were video works. And Benjamin was teaching this one course on video technology (waveform monitors, vectorscopes, etc.) which I found absolutely wonderful. His approach was about developing the art through really understanding the technology.

But media arts centers were actually few and far between in the US. Philadelphia did not have a media arts center. There was no BFVF there. Also, I had partially edited my thesis film in New York City at another media arts center, Young Filmmakers on Rivington Street. They had three-quarter inch U-matic video editing systems, which you could rent for an hourly fee. So I edited my thesis between Young Filmmakers and in Boston, going back and forth. When I moved back to Philadelphia I realized we didn't have the kind of center where videomakers could come together or where people could have equipment access. That was one of the germs to the idea, "OK, well, why not?"

It began by just knocking on doors and introducing myself to folks in film collectives in Philadelphia. There was a really wonderful exhibition program, that still exists, at International House, it's now called the Lightbox Film Center. It was programmed by Linda Blackaby. There was a collective called New Liberty, with a very generous filmmaker Lamar Williams. Also, there was a very influential film programmer, Oliver Franklin, who was extremely helpful to me in moving back to Philadelphia. He connected me to the Pennsylvania Council on The Arts, which was trying to see how a media arts center could be established in Philadelphia.

Scribe Video Center in the year 2000, the Documentary History Project for Youth.

Scribe started very modestly. My day job was working as a staff producer at the public TV station in Philadelphia, mainly directing documentaries for local broadcast. Nights and evenings I'd offer workshops in video technology and production. I borrowed the Xeroxed handouts that Benjamin Bergery [at MIT] had put together. The people that came to Scribe were oftentimes artists in other media. The workshops were either free or low cost, We were given free space at Brandywine Workshop, a fine arts print atelier on Kater Street.

We were realizing, that although we were definitely ethnically, racially, gender-wise diverse, the folks using Scribe tended to be people in the know. We [began to wonder] how do we enlarge the circle to people who don't necessarily give themselves permission to create? Often, for working-class people, if there is going to be any cultural offering or opportunity for cultural expression you think about it for the children. Oftentimes adults don't give themselves permission to engage in creative processes.